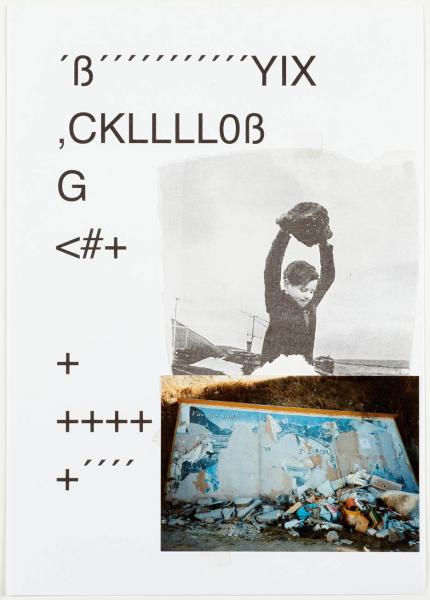

cultural collages

the assembling principle in Dominik Steiger's work (excerpt)

Brigitte Huck

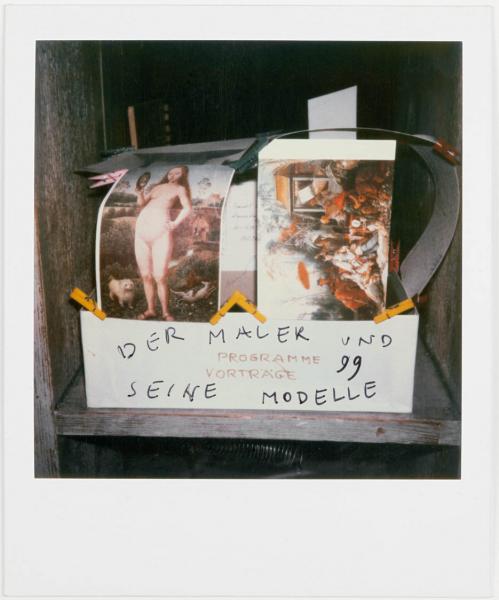

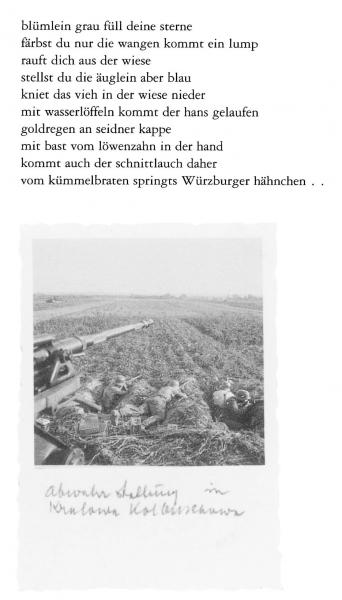

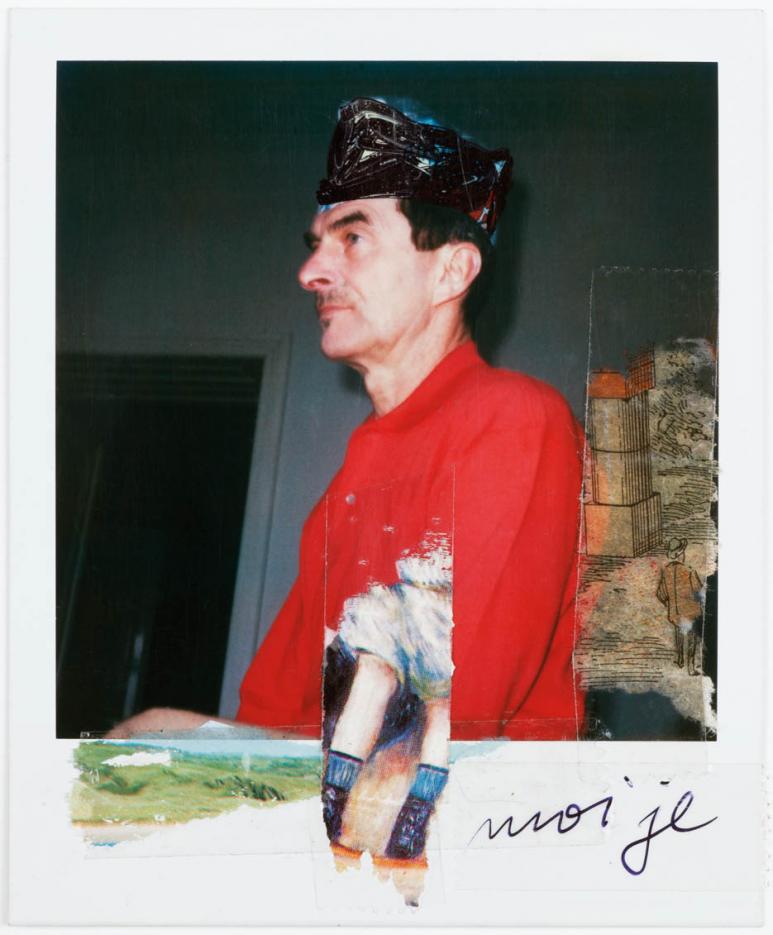

moi je, ca. 1999. Tixo-Collage, Permanent-Marker on polaroid, 10,8 x 8,8 cm

August 2012. It is a balmy summer evening in the Augarten in Vienna. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Foundation hosts another evening in its performance series Ephemeropteræ. Studio, exhibition space and the park are transformed into a setting of the time-bound, the ephemeral. In short episodes music, poetry, literature and song happen in the twilight.

Dominik Steiger sits at the edge of the stage and reads. A pastiche of texts by various authors in all kinds of languages and various works of his own. His co-celebrant Gilbert Bretterbauer (*1957), like himself committed to an experimental approach to the literary and the visual, has equipped the open-air stage by British architect David Adjayes (*1966) with a textile backdrop staggered in depth. (...)

At some point, Steiger gets up and takes an LED headlamp from a suitcase he brought, casually standing in the meadow. He puts it on. Then he stands in the backdrop aisle behind a cut-out at head height and continues reading, holding the book through another decoupage in the curtain. With the layers of textile-artist-book-textile plus the microphone in front of and the lamp in the artist's face, the principle of collage is almost literally transferred into the third dimension: a work example of patchwork as a form of action, a 3-D sound and image sampling - and a form of "cadavre exquis" to boot, when Gilbert Bretterbauer leaves the use of his textile default to coincidence and the surrealism-savvy Dominik Steiger. Steiger crowns his study on "How do I perform collage?" with an ironically patched jacket. As guild clothing, he wears a blue work jacket painted on the back: Selber Schmonzes (nonsense yourself) is written there. You thought to see tailcoat peplums made of cotton dirndl fabric, boldly fluttering in the wind. But it was the wife's blue and white patterned bathing costume, misappropriated for the layered look.

Still from the video documentation of the spoken word performance by Dominik Steiger in context of der Veranstaltungsreihe Ephemeropterae ˜ X / XV+, TBA21–Augarten, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Wien, 17. 8. 2012

First of all, the principle of collage presupposes another cultural technique: that of collecting. Dominik Steiger is also a collector and saves everything that might sometimes be artistically usable: old photographs and postcards, wood scraps from carpentry shops, packaging from the supermarket, coins, stones, various bottles with and without their cartons, auction catalogs, newspaper advertisements, custom-made shoes, even shower curtains and a zither or rolling pins used as paint rollers - in Vienna they are called Nudelwalker. (...)

text (...)

In the layer work of the shifter Dominik Steiger, literature, fine art, music and life overlap. His work indeed is distinguished by a progressing concept of collage, with different levels of his work interweaving beyond pure matter into time and space. Drawings and objects, language and thinking emerge in a parallel process. (...)

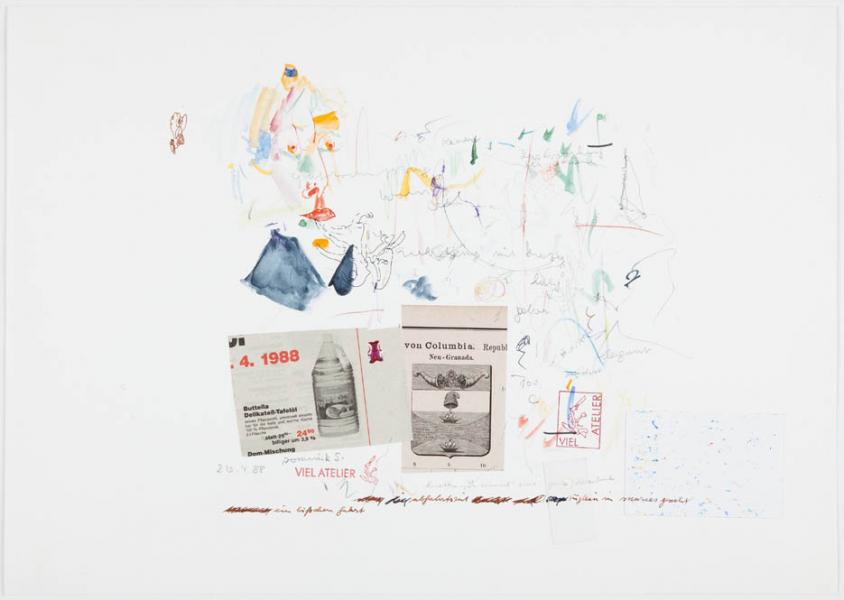

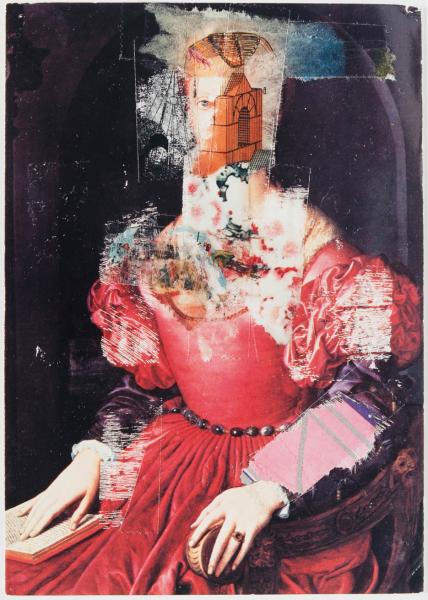

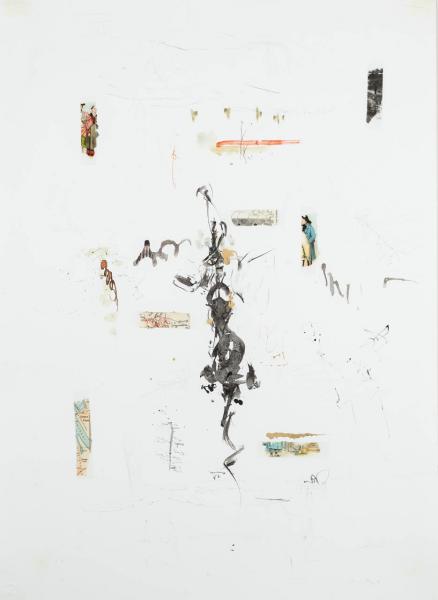

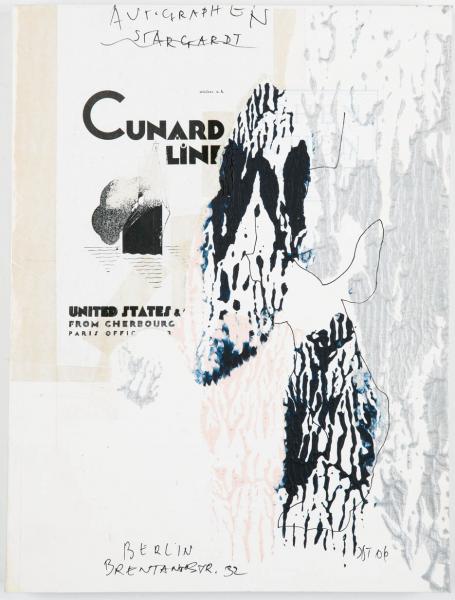

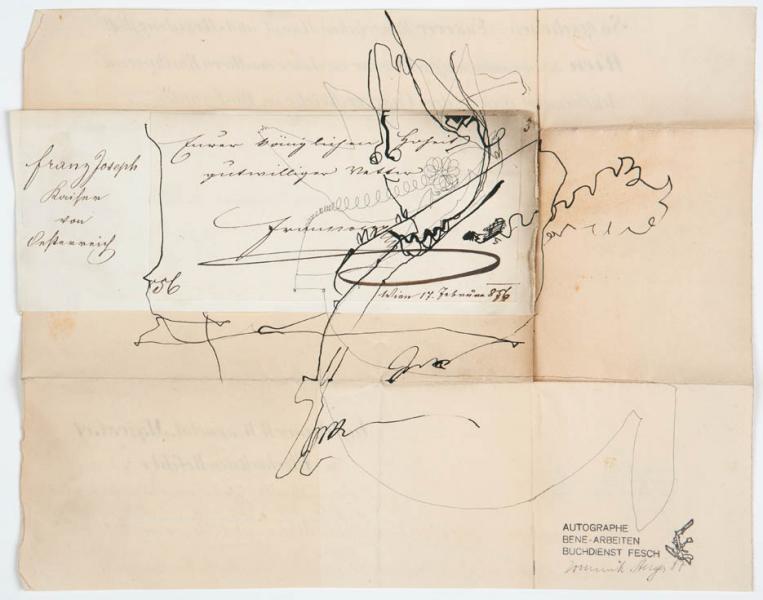

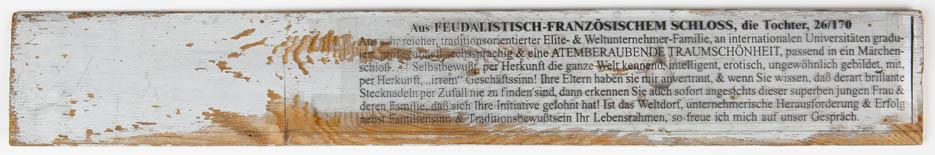

Du to Steiger's interest for organizing pictorial spaces as stage for scribblings and bricolage, as reservoirs for history, memories and poetic brainstorms, major parts of his oeuvre can be classified as collage. It is a genre, which Steiger calls cultural collages, Kulturcollagen (fig. 2+3/8), or sometimes conversation graphics, Konversationsgrafiken (fig. 4+ 5/8). For his series – consisting of reworked auction catalogs (fig. 6 + 7/8), this technique is as significant as for the group of wooden sculptures called Bois the polaroids (fig. at the top), the assemblages of packaging material and other found objects, the Autographe Bene works (fig. 8/8) and the so-called Exzerptmarterln: collages of ideas on A4-sheets, for which Steiger uses classical methods of conceptual art.

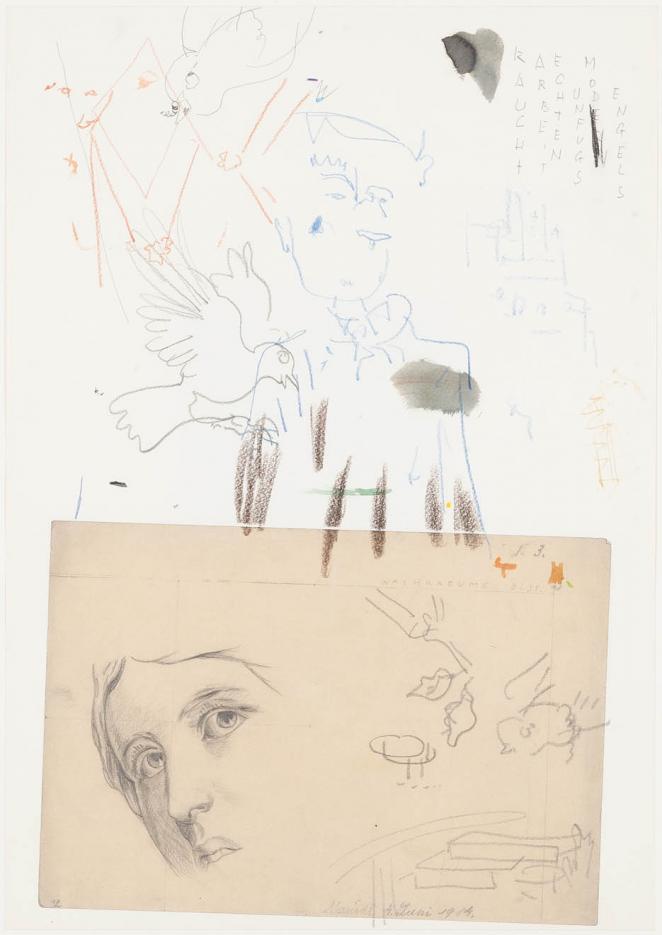

NACHRAEUME, 1990. Using a drawing (1914) by Maria Fridinger. Collage, mixed media on paper, 48 x 34 cm

Carefully Steiger stores everything which could be of use, be it the Encyclopaedia Britannica or coloured pencil sharpeners. He collects these resources in his studio, which before him was used by Maria Fridinger (ca 1900-1990), daughter of Art Nouveau artist Josef Engelhart (1864-1941). When she died aged 90, Dominik Steiger took over the room, including much of its content: sketches, drawings and water colour paintings of the old lady, including some geometries of her husband Egon (1896-1970) who was an architect. „The papers (…) inspired me“ Steiger writes under the title Marie Maridl Mariechen and I, „to make combined pictures in various techniques in spite of a certain psychological resistance. Working from segments or cuttings to collage or de-collage, assemblage, recycling, quotation, extension, reduction, also displacement, ornamentation to literarization“2 (fig. above). (...)

Aufgetakelter Schuh, 1984. Men's leather shoe, wood, metal rods, shoe paste and felt-tip pen on cotton undershirt (signed, dated and titled „Thingummy, Thingumabob, Thingumajig. Budi St. 81–84“)

If Andy Warhol put his stuff in boxes, glued and stored Time Capsules, if Francis Bacon (1909-1992) had to physically feel his resonating material, throw it into the big space box of his studio and shuffle over it, Dominik Steiger carefully arranges his materials into sculptural ensembles. The shelves, credenzas, crates, and double-window display cases of his private studiolo - akin to the Renaissance type of space and dedicated to active study and contemplative reflection - are crammed with works in various degrees of completion. One could never be sure whether the undershirts with the shoe pasta stains would end up in the trash or come to hang proudly like the main sail of the Mayflower on the wire mast above the shoe boat (fig. above).

In spite of all evident vicinity to allegories and optic discourses about the concept of collecting, the artist's intent was not only to put images on stage. In the cognitive laboratory of Steiger with its striking view on the ominous Flak Towers, everyday life in a world of products plays a lesser role than mental and immaterial references behind the objects the installation is made of. The seductive idea to fill art into a room for thought, just like inlays of Pietra dura, the encounter of production site and presentation creates the kind of beauty of which the French poet Lautréamont (1846-1870) speaks, when sewing machine and umbrella meet on the dissecting table. (...)

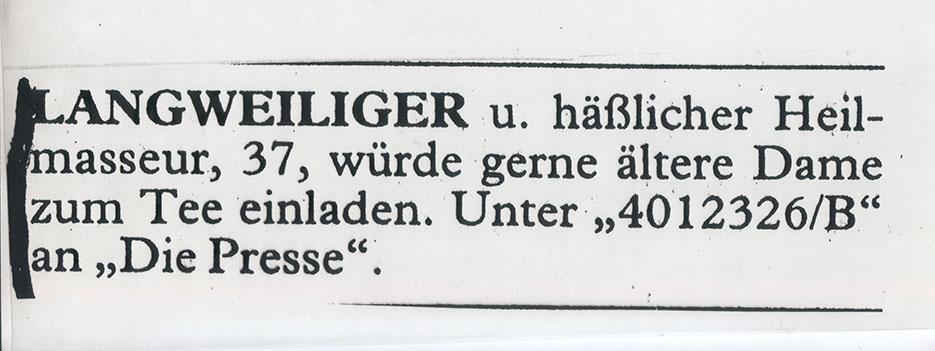

Searching across the various phases of the work, one finds bottles filled with printed transparent sheets (fig. 3/5). Steiger discovered the newspaper ads to be read on them in serious daily newspapers such as Die Presse - and so such puns as "Boring and ugly medical masseur, 37, would like to invite an older lady to tea" (fig. 4/5) go down in art and literary history. There are several paper fruit cups from supermarket shelves. Steiger paints and glues them with small black-and-white photos of cities and landscapes, puts old photographs in the flaps. The city of Prague or the Pulvermaar in the Eifel, little brothers and sisters sitting in a made-up trash boat. (fig. 1+ 2/5)

The term bricolage goes back to the French ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009), who introduced his concept of "wild thinking" - taking and linking what is there - to the social sciences in 1962. A tinkerer, according to Lévi-Strauss, combines what he has at hand. Instead of inventing something new, he transforms what exists so as to put it together in an individual way. Overlaps of different sign systems are the basis of the typology and the different procedures of the medium. (...)

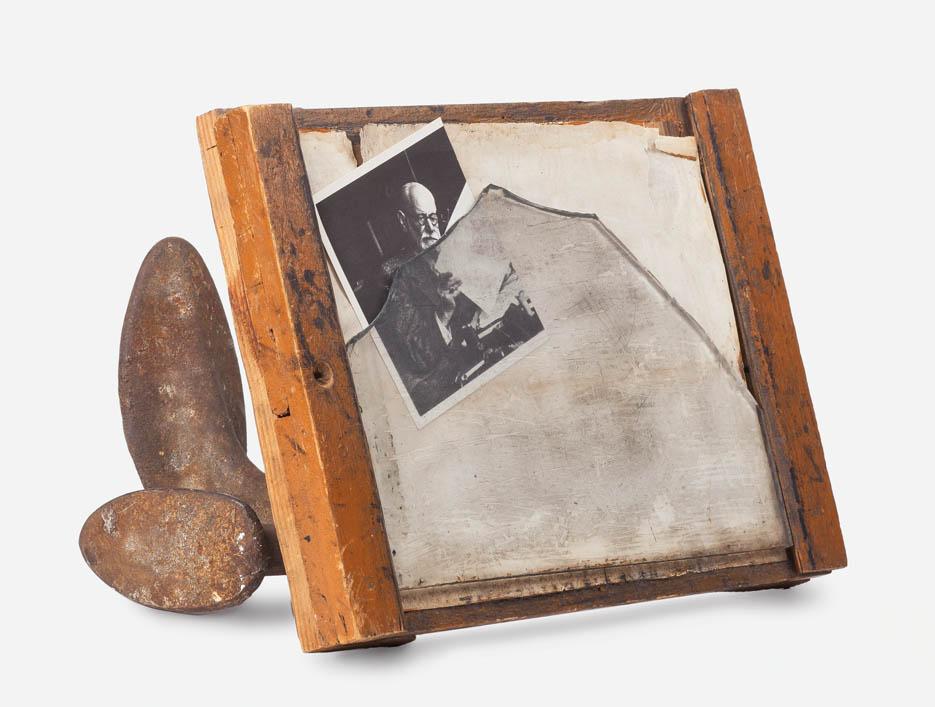

à tel hier, 1994. Black and white foto behind glass, wooden frame, awl loodely added, different sizes

A portrait photograph of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) is inserted behind the blind glass pane of a wooden frame construction and documents Steiger's interest in Freud's theories. "That a poetics close to Freud, which finds its forms by working on the material of words and signs, means work of thought or imagination overcoming inhibitions [...] will not be surprising in view of Freud's theories.“ 8 Furthermore, the rusted cobbler's anvil, against which the frame leans, refers to elegant footwear and shoemaking, which are indispensable to this artist's life: "[...] go alone [...] to istanbul. look for job as sailor. end up with austrian mission [...] through their mediation employment as correspondence assistant with shoe merchants“.9

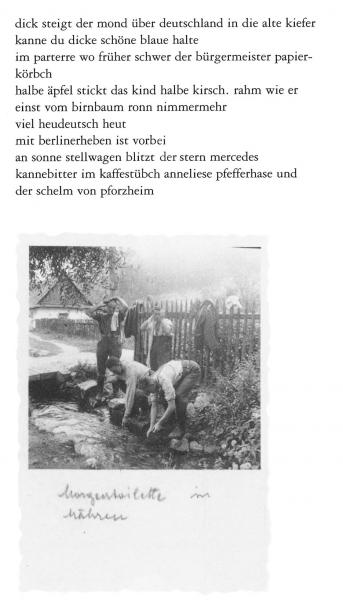

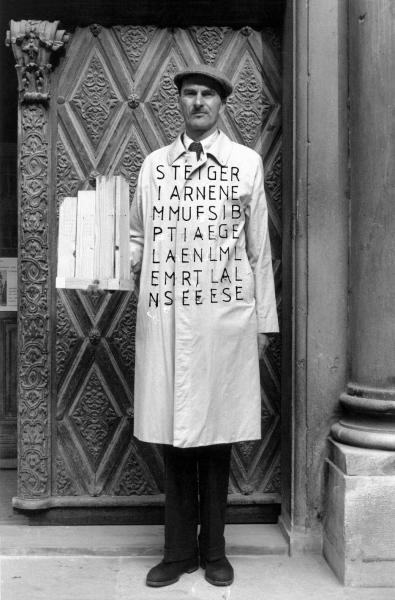

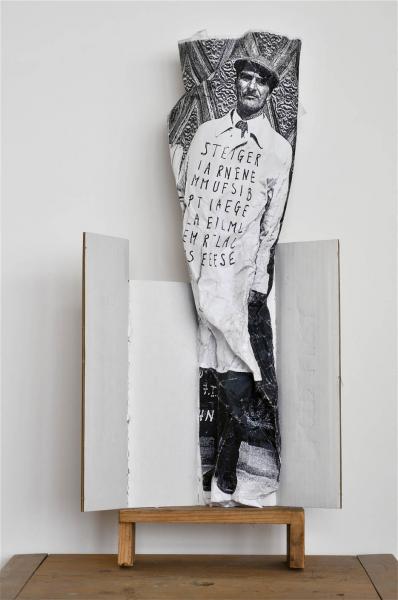

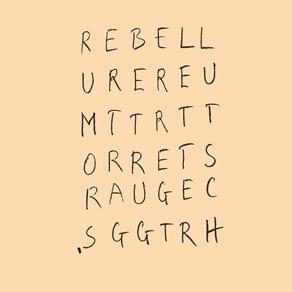

A photograph of the artist as Homme de lettres in raincoat and flat cap in front of the portal of the early baroque Jesuit Church in Vienna's 1st district appears in various contexts (fig. 3/5). The Burlington is painted with a letterfall, a typography in which the letters of the word in the first row, vertically continued, form further words. 1991 Steiger mounts this literalness on the wooden object "Effort" (fig. 5/5), or stuffs it, slightly squashed in a paper tube (fig. 4/5). Trimmed and mounted on paper, military-historical autographs form the basis of a spirited scribbled drawing which almost looks like scripture. Reminding the typical Klimt timbre Steiger mounts a photo of Joseph Beuys – shot while walking together around in Vienna – with magazine clipping and black and gold wallpaper on cardboard (fig. 2/5); or he combines the first computer-typing attempts of his son Moritz Ganser (*1997) with a newspaper cutting of a young Hercules and the foto he took of a garbage heap in front of a poster wall saying "for the soul". (fig. 1/5)

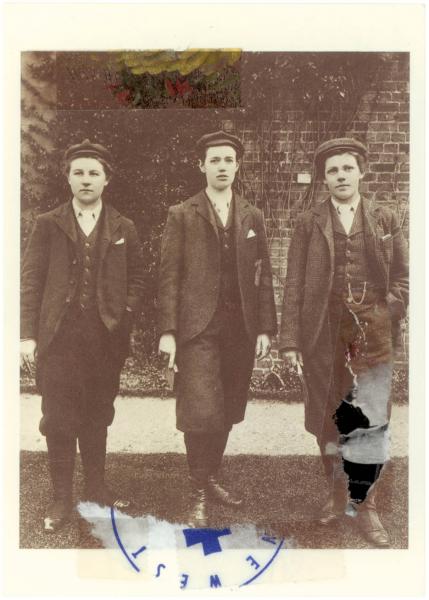

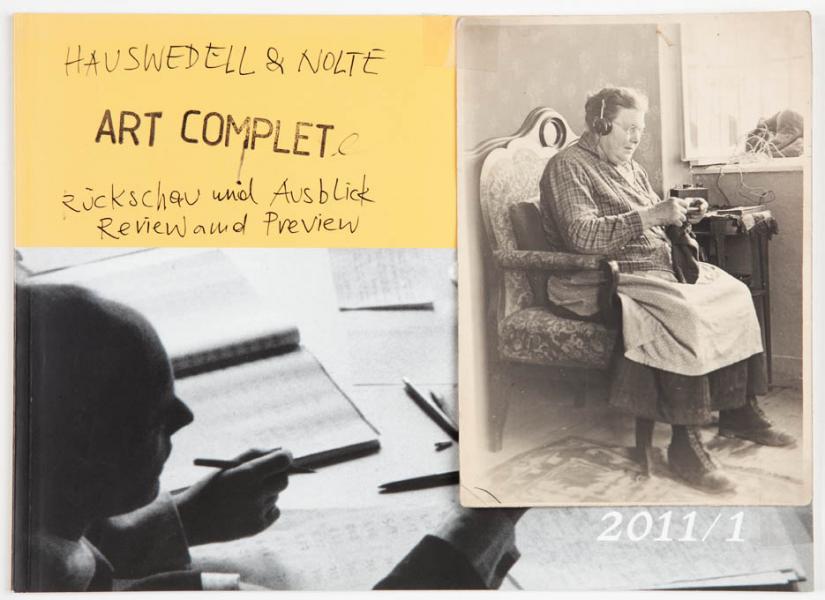

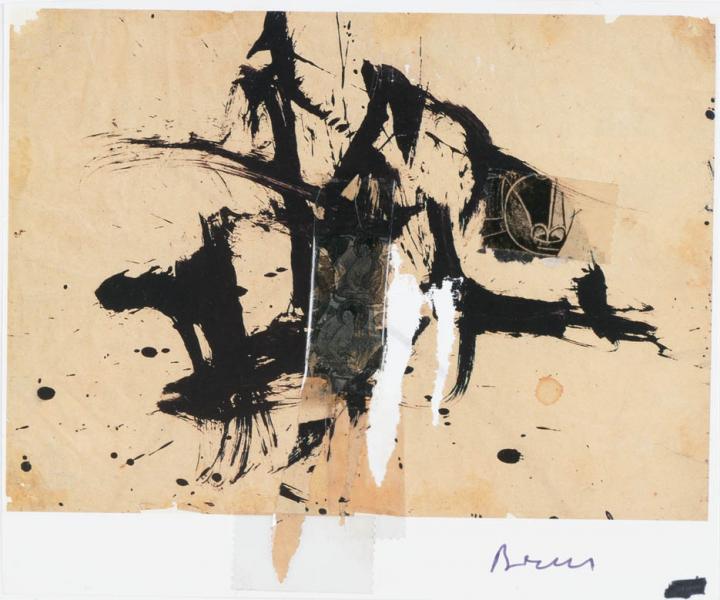

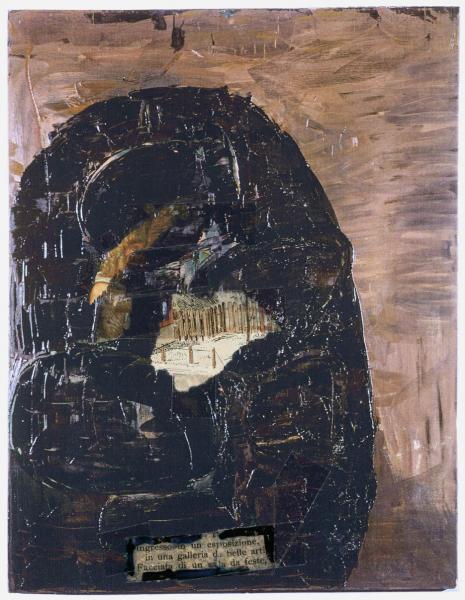

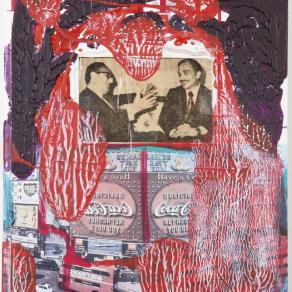

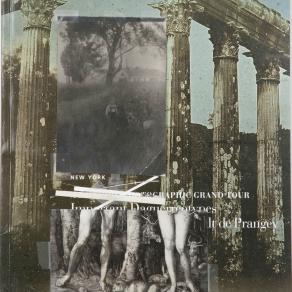

The amelioration of auction catalogs in the series Art Complete confronts reworked covers with collages and de-collages, as for instance the upside down image of the artwork Grünocker I (1992) by Kurt Kocherscheidt (1943–1992), pasted up with a small newspaper tear off telling of a „galleria di belle arti“ (fig. 2/2), or an abstract ink drawing from the 1960ies mingling with the actionist oeuvre of Günter Brus (*1938). (fig. 1/2)

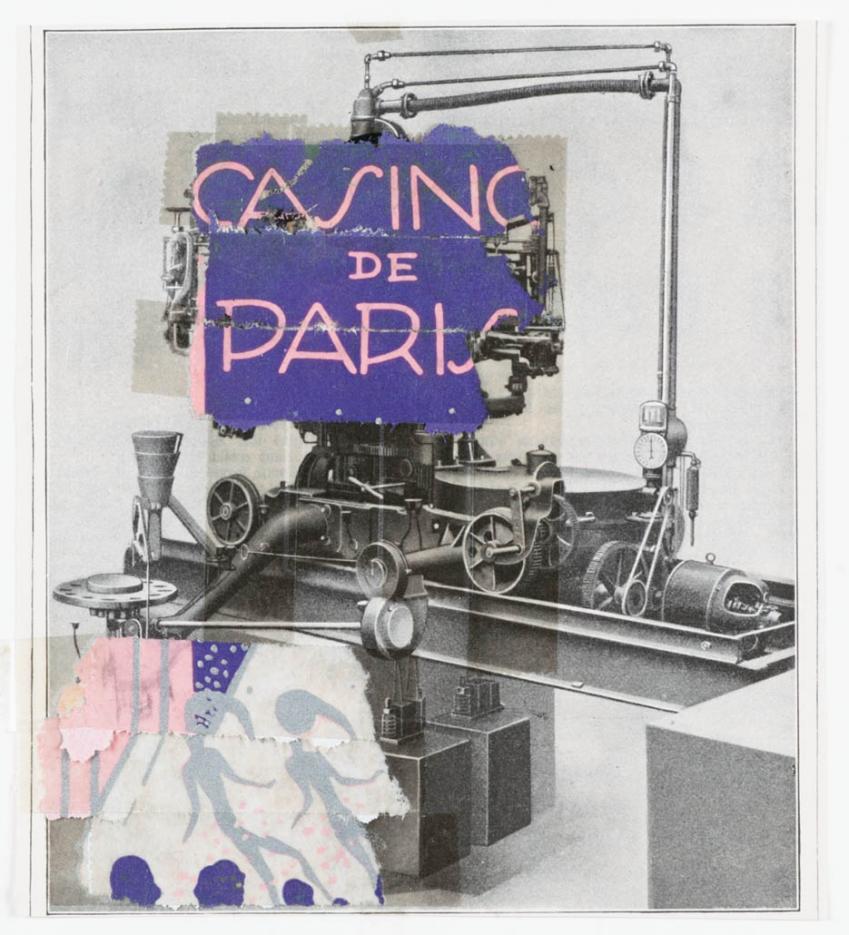

Untitled (CASINO DE PARIS), undated. A.o. using a program booklet (1929) of the Casino de Paris revue theater. Adhesive tape-collage on b/w illustration (magazine clipping), laminated on cardboard., 21,6 x 20 cm

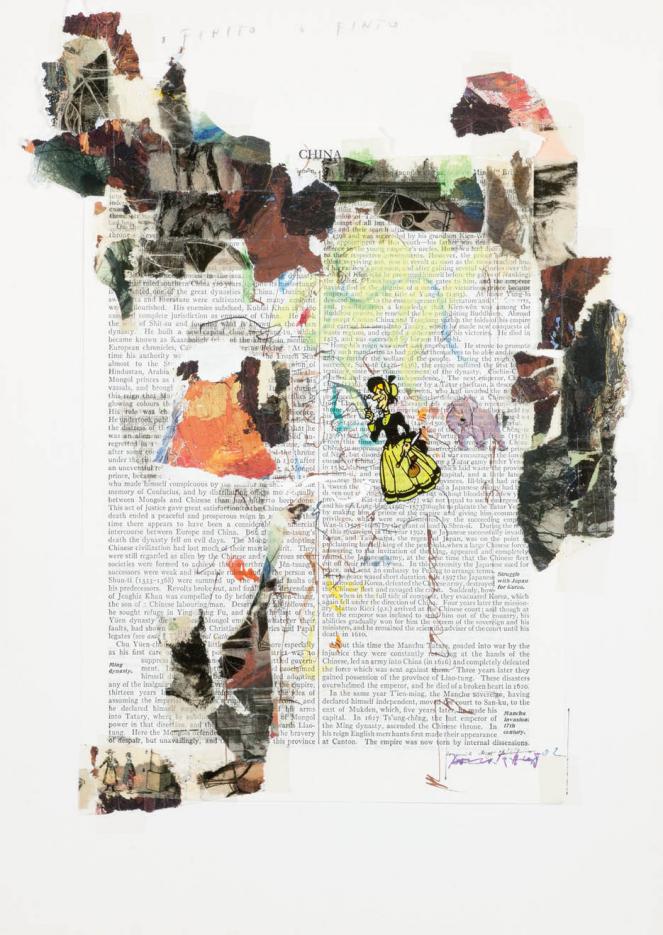

He paints over private photos from friends, inscribes polaroids and small tachist watercolours with acronyms, acrostics and alliterations. The combination of the illustration of a Casino de Paris program booklet from 1929 with a steam engine (fig. 294) allows associations with Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the master of cross-references, with erotism, with technology and the liberation of everything unambiguous in art. He completes fine drawings on the thin paper of the Encyclopædia Britannica, rendered with a pointed pen, with scratch-off pictures of comic figures and adhesive tape, called "Tesa" in Germany and "Tixo“ in Austria. Tixo-tics, the transfer of thin layers of images by means of transparent adhesive strips, is a technique Dominik Steiger developed in the 1990s for his cultural collages.

FINITO FINTO, 1989/95/2002, from the series Kulturcollagen (culture-collages). Using a page from the Encyclopædia Britannica. Adhesive tape-collage, ink, scratch transfers on cardboard., 29,5 x 21 cm

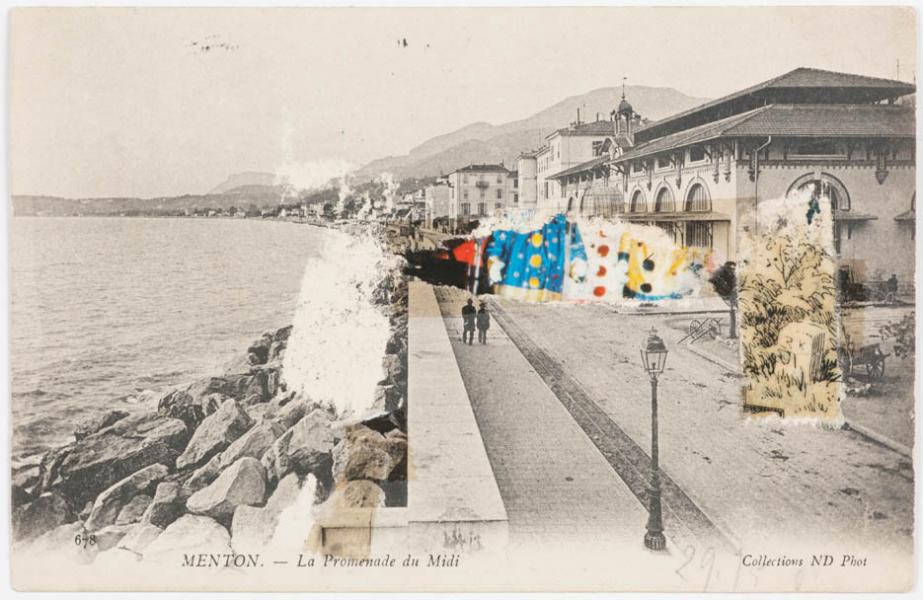

Kulturcollagen (a term rumored to be attributed to Steiger's gallerist Julius Hummel) are mainly historical postcards that Dominik Steiger and his wife Traudl (1922-2007), widow of the legendary literary figure Konrad Bayer and queen of the Viennese art scene, receive from friends and acquaintances. The architect Luigi Blau (*1945) is among them, the art dealer Kurt Kalb (*1935), the illustrator Mia Williams alias Marie Luise Löblich (1928-k. A.), or the (at that time) notorious US-American erotic artist Dorothy Iannone (*1933), who is on the road with Dieter Roth (1930-1998) in the 70s. These are just a few of the senders. They all send beautiful cards from the depths of flea markets and souvenir stores of this world.

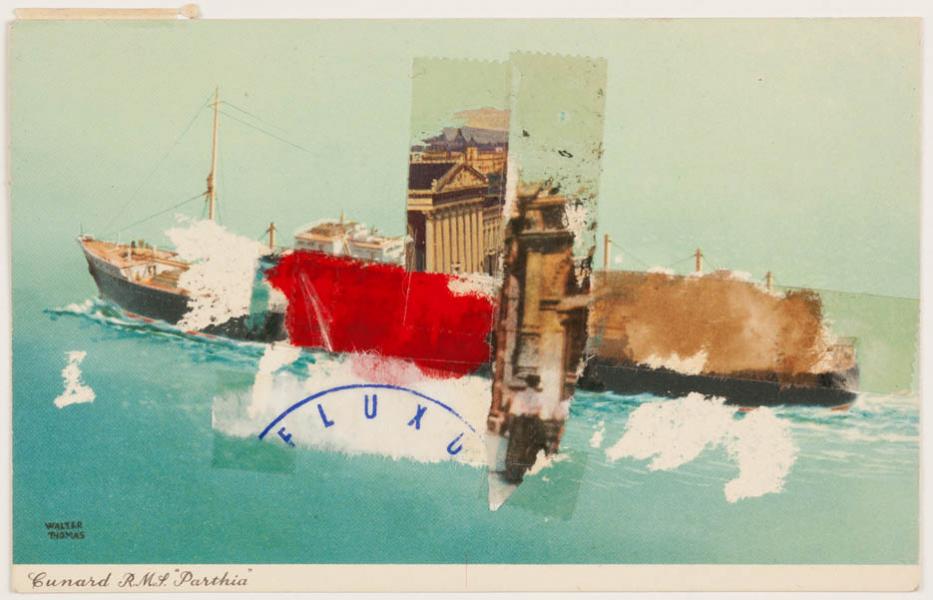

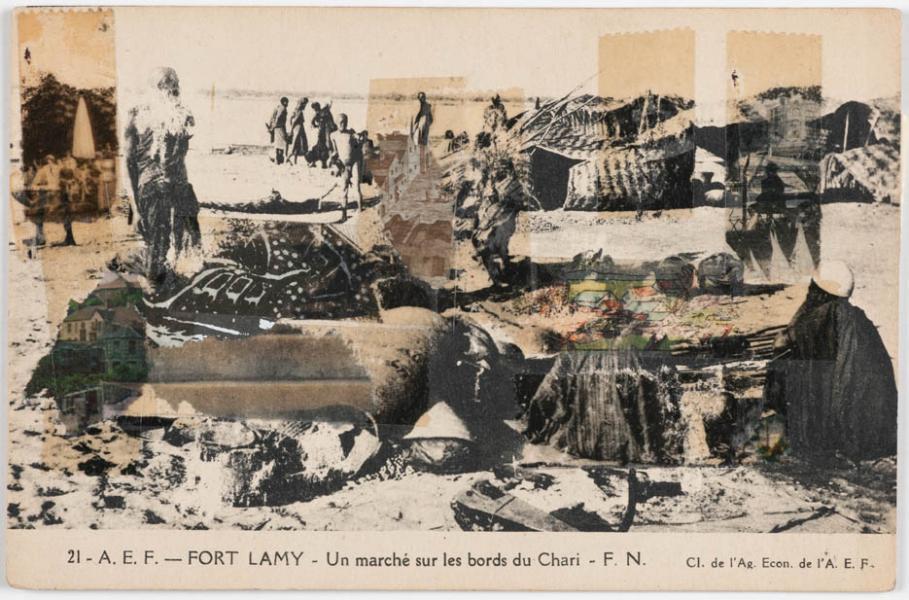

Steiger chooses suggestive motifs that arouse curiosity to work with: the beach promenade of Menton, the "pearl of France," as Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) called the little town (fig. 1/3); the RMS Parthia of the tradition-steeped Cunard Line, Katharine Hepburn's (1907-2003) first choice for ocean crossings (fig. 2/3); or the huts on the Chari River outside Fort-Lamy (fig. 3/3), the capital of Chad. On the postcards, daily life merges with absurdity and coincidence. Steiger transforms the motifs through mechanical image transfer, thwarts visual habits, expands perception: on the Cunard Lines advertising postcard, the steamer plows through white spray created by scraping up and scraping off the paper; it is loaded with an architecture of construction containers - strips of adhesive tape that exchange surfaces and transfer information. Steiger uses the Fluxus stamp to evoke action art and the artist's book. At the same time, he alludes to the anti-bourgeois and anti-commercial attitude of the Fluxus artists. And to their anarchic freedom, to which he, like them, is committed.

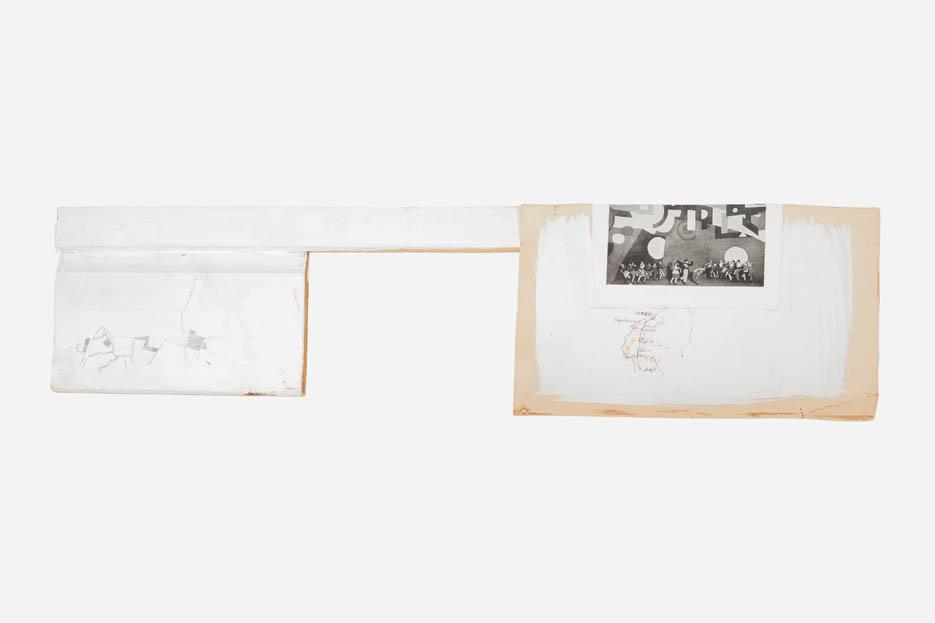

Point of departure for a series full of ironic allusions - wooden assemblages called Bois - is his encounter with Joseph Beuys. In December 1971 he comes to Vienna at the invitation of Oswald Wiener (*1935). "Wiener wants to show Beuys the Waldviertel," Steiger remembers in his text Gast Beuys 10 and continues "Wald bois," (the french word bois meaning wood and forest/Wald in German), thus determining the title of his wooden sculptures. The fact that the Viennese pronunciation of "bois" echoes the name Beuys in an onomatopoeic way confirms his choice. The said "was quartered with us, Traudl Bayer and me, in a small [sic] cabinet. [...] The first time we came closer was when Beuys noticed that Traudl was cooking beef tongue for lunch [...] O. W., as usual swarming at night, was unable to travel for three or four days"11, a time that Steiger spends with Beuys. Steiger follows Beuys's instruction to fill an empty wooden box, the 1968 Multiple Intuition, with meaning: "For my first bois I fished out throw-away pieces form a wastpaper basket, after craftsmen worked in my studio, and inserted them into his multiple box intuition with post-Beuysian verve." 12 (fig. 2/3) Later Bois objects remind of birds or ships, one even with a sail made from a colour palette (fig. 3/3). (...)

Steiger picks his blocks and strips from carpenter's waste with deliberate dexterity. He glues them together to form open constructions. He emphasizes the strategy of multiple views by sticking collage elements on them. (...)

Craft perfection is not his thing, just as little as modular regularity and the principle of the series. Rather, the anti-aesthetic attitude in Steiger's sculptural work is committed to the unwieldy, the used, the distance from tastefully polite procedures. All the more universal are the materials he uses for his montages: encyclopedias, reference works, catalogs, dictionaries - and again and again postcards and art cards, which are semantically tremendously charged and pursue a linguistic rather than a merely formal idea. In contrast to antinarrativist, classical conceptual art, Steiger's collages, montages, and combines are oriented toward the aesthetic regime of a poetic subjectivity. They remain in the psychological, private space of artistic production and are thus "separated from the functionalizations of the social and political. "13 It is however precisely because of this non-public aspect, that the political potential and intellectual principles of Steiger's work are released.

"There are no answers, only cross-references "14 -the "Law of Libraries" by the American mathematician Norbert Wiener (1894-1964) also characterizes Dominik Steiger's collage work: a coherent chain of references, quotations, wordplay, and image fragments, presented within the code of visual art.

Untitled (FUKUI), undated, Wooden object with cartographic drawings. Paint, ink on wood, loose supplement: collage, opaque white, ink on cardboard, 16,5 x 60 x 2 cm,

1 Dominik Steiger | 60 Jahre | Tisch Traum a, published in the context of Interventionen in progress 13 by museum in progress, in: Der Standard, 19. 9. 2000, p. 13.

2 Dominik Steiger, Marie Maridl Mariechen und ich, in: the same, Thingummy , Droschl, Graz/ Vienna 1994, p. 141.

3 Ferdinand Schmatz, Zu Dominik Steigers Arbeit der Aufhebung. Oder: Das Gesamtkunstwerk kann nicht nur eines sein und niemals ganz, in: Dominik Steiger, Aufhebung der Arbeit, Buchdienst Fesch – Tagtraumarbeiterpartei, Vienna 1993, leaflet.

4 Dominik Steiger in a conversation with the author, summer 2004.

5 Dominik Steiger, Idyllen , Bagatellen , Mehrchen , Nimermehrchen , Iduart u. Letterspeck , Fotos : Max im Krieg , bissl Leben (siehe dort ), in: Otto Breicha (ed.), Protokolle ’89/1. Zeitschrift für Literatur und Kunst, vol. 1, yr. 1989, Jugend und Volk, Vienna/ Munich 1989, p. 97–112.

6 Dominik Steiger, Anmerkung zu „Idyllen , Bagatellen [...]“, in: the same., Thingummy , Droschl, Graz/Wien 1994, p. 371.

7 ibid., p. 158.

8 Benedikt Ledebur, Das Kosmöschen in chaotischer Auslese. Zum literarischen Werk Dominik Steigers unter Bezugnahme auf Sigmund Freuds Untersuchung „Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten“, in: kolik. Zeitschrift für Literatur, Nr. 50, December 2010, p. 24.

9 Dominik Steiger, künstler-nativität, in: the same, Thingummy , Droschl, Graz/Wien 1994, p. 158.

10 ibid, p. 144.

11 ibid.

12 Dominik Steiger, Untitled, incipit: "Inspired by A. Thomkins," in: ibid, p. 134.

13 Susan Hiller in conversation with Jörg Heiser and Jan Verwoert, in: Jörg Heiser (ed.), Romantischer Konzeptualismus, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthalle Nürnberg/Bawag Foundation Wien, Kerber, Bielefeld 2008, S. 29.

14 Norbert Wiener (Original: „There are no answers, only cross references“), in: Pesi R. Masani, Norbert Wiener 1894–1964, Birkhäuser, Basel 1990, p. 337.

Article first published in: exhibition catalog DOMINIK STEIGER RETROSPEKTIVE, Kunsthalle Krems, 2014, editor: Hans-Peter Wipplinger, concept Suse Längle and Hans-Peter Wipplinger, 2014, Verlag d. Buchhandlung Walter König, p. 272-281

Translation: Renate Ganser